1861

June 13, 1861: The Third Michigan leaves Cantonment Anderson, south of Grand Rapids for Detroit. They leave with 1,040 men in ten companies.

June 16, 1861: The Third Michigan arrives in Washington City.

July 1, 1861: The Third suffers it's first casualty. William Choates of Company C dies of fever.

July 18, 1861: The Third comes under fire at Blackburn's Ford during the First Battle of Bull Run.

July 21, 1861: The Third assists in covering the retreat after the Battle of Bull Run.

Third Michigan History

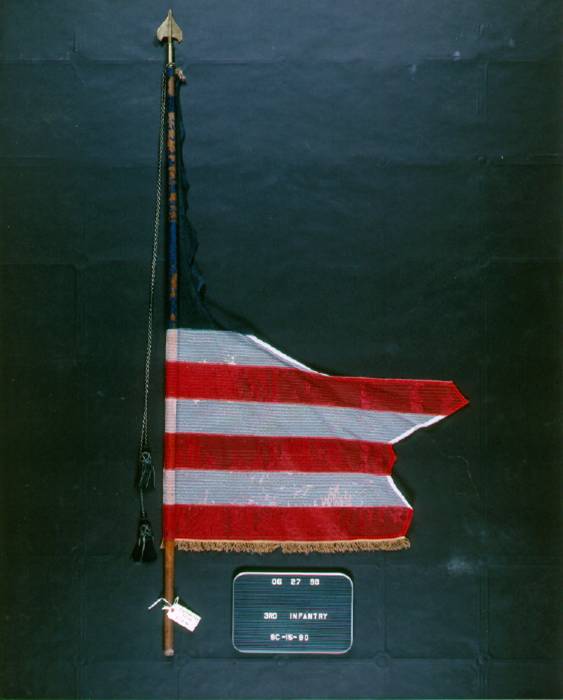

Third Michigan National Flag

1862

April 4,1862: Siege of Yorktown

May 5, 1862: The Third assists in driving back a Confederate counterattack at the Battle of Williamsburg.

May 31, 1862: Fair Oaks, Virginia

June 29, 1862: Savage Station, Virginia

Peach Orchard, Virginia

June 30, 1862: Glendale, Virginia

White Oak Swamp, Virginia

July 1, 1862: Malvern Hill, Virginia

August 29, 1862: 2nd Bull Run

September 1, 1862: Chantilly, Virginia

December 13, 1862: Fredricksburg, Virginia

Third Michigan Infantry

The Third was formed at Grand Rapids from

companies raised in the area, as well as from

Lansing. It was mustered into service on

June 10, 1861.

CHARLES T. FOSTER

One of the volunteers was a young clerk in a Lansing dry goods store named Charles T. Foster. His younger brother, Seymour, remembering Charles many years after the war, described him as about five feet ten inches in height, with a light complexion, big blue eyes, and a high forehead. He was a fine singer, a member of the church choir, had a genial disposition and agreeable manner and was a great comfort to his widowed mother. He wore a very becoming young mustache.

Charles had attended a mass rally at the old capitol in Lansing the day after the attack on Fort Sumter. The House chamber was packed. Cheer after cheer and speech after fiery speech filled the air in the packed hall and then a call for volunteers to fight to save the Union. Not a soul moved. Then Seymour, who had not been able to get into the packed hall and had climbed up and perched in one of the windows, saw that someone was working his way to the head of the crowd. He couldn’t see who it was. Suddenly, a voice rang out: “Charles T. Foster tenders his services and his life if need be to his country and his flag.” Charles had just become the Lansing area’s first volunteer. But since there were no regiments forming in Lansing, he had to go to Grand Rapids to join.

On June 4, 1861—just before the regiment left for battle—a vast assemblage of people—at least 4,000—gathered at the Third’s training camp on the outskirts of GR to watch a moving ceremony in which 34 young women, representing the states of the Union, presented the regiment with a beautiful silken banner.

REBECCA RICHMOND

Grand Rapids had been overwhelmed by “war fever” and one of the belles of the town—a young woman named Rebecca Richmond—kept a diary which vividly described how the city had rallied to send “their” regiment to war. Rebecca had been one of the “ladies of Grand Rapids” who had raised the money for a special flag to be presented to the regiment. A correspondent for the Detroit Daily Advertiser visited Grand Rapids shortly before the ceremony and wrote this report:

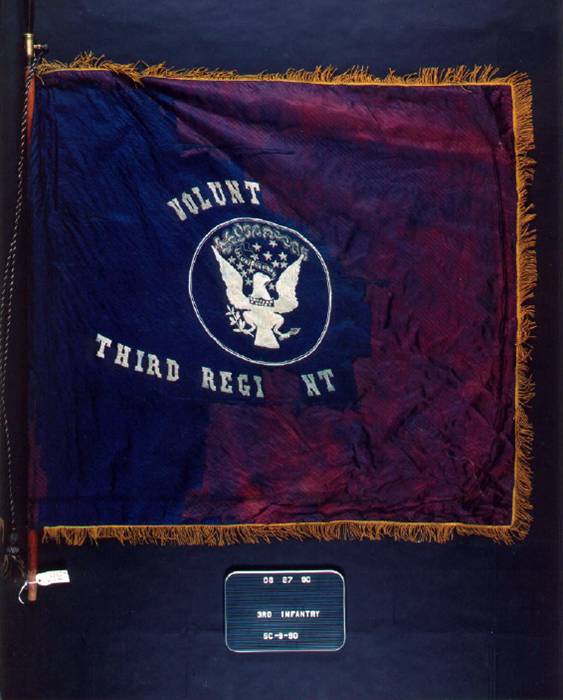

“The flag is of the army size, six feet on the pike and six feet six inches on the fly, of blue silk, with heavy yellow fringe, and on the front is elegantly embroidered in corn-colored silk, the arms of the United States and the words “Volunteers, Third Regiment, Mich.” surrounding the arms.

Upon the obverse appear the same arms and over and under them the words “The Ladies of Grand Rapids to the Third Regiment Michigan Infantry,” also embroidered. The work is of the most delicate and substantial kind. The embroidery is beautiful, the work of Maggie Ferguson, of our city, and the whole is attached to a pike ten feet long—it is a beauty and reflects more than ordinary credit upon the generous ladies who got it up.”

Carriages brought the 34 girls to the camp, as well as a huge cavalcade of spectators, a brass band, and a glee club. Six girls—including (of course) Rebecca—presented the flag to the regiment. Rebecca’s diary tells us that the girls wore blue dresses with red and white sashes, and carried blue parasols with 13 gold stars. The other girls wore red Zouave jackets and brown jockey hats trimmed with red, white and blue. Then three cheers for the “Ladies of Grand Rapids” and three cheers for the flag.

THE THIRD DEPARTS

A few days later, Rebecca recorded in her diary: “June 13—one of the saddest days in the records of Grand Rapids. Our pet regiment, the Third, has departed at last and left many, many sorrowing hearts.” As the regiment marched away, thousands waved handkerchiefs and young girls showered the troops with bouquets.

The gaiety was short-lived. On July 2 Maggie Ferguson died of consumption. The Grand Rapids Enquirer noted that “her hands were last employed in embroidering the banner presented to the Third Regiment.”

There was no time to mourn her. On July 18, 1861, the regiment was plunged into battle at Blackburn’s Ford and—only a few days later on July 21—they were at Bull Run.

Charles Foster survived Bull Run. He fought with the Third for the first year of the war. Then, at the battle of Williamsburg in May 1862, Foster volunteered to carry the flag when the regular color sergeant was unable to do so. He wrote his mother the next day:

“When the Major called for volunteers and none of the sergeants seeming to want to take the responsible and dangerous position, I felt it to be my duty to do so, for someone must do it, and if none would volunteer a detail would have to be made, and the lot might fall on one who had a wife and children at home and could not be spared, whereas I was single and free, and would not be missed if I was killed.”

A few weeks later, at the Battle of Fair Oaks, Foster was called upon again to carry the flag. He did so, through charge after charge. Suddenly, a minnie ball pierced his neck. As he fell, he called out “Don’t let the colors go down!”

Writing his memoirs, Ezra Ransome remembered that moment: “I rescued the colors from capture. The bearer had when shot fell on his back and threw both arms in a death grip around the flag just as our line had fallen back a little, which left the colors between the rebs and us. I rushed for the flag, pulled it from the arms of the Sergeant, fell flat and so dragged myself back to our men.”

Charles’s brother Seymour recalled that Charles never knew the grief his letter caused their mother, particularly his statement that he would not be missed.

By March 1863, the flag had become so tattered that the regiment was forced to retire it from active duty. It was brought home to Grand Rapids by Captain George Judd, who had lost an arm defending it. With the flag came this letter, written by Colonel Pierce:

“Dear Sir—I have the honor to send to you the banner presented to this regiment by the Ladies of Grand Rapids. My reasons for returning it are that is has been the rallying point around which we have gathered in so many battles, and having stood the brunt of them, has become so tattered and torn that we have concluded to place it on the returned list. You will see by its dilapidated condition that it would be impossible to carry it beyond the battles in which we have become engaged—and I am proud to say that it has ever been defended to the last. Its fair folds have been baptized by the blood of many brave and gallant soldiers—Have it placed in safekeeping, so when we return, we may again rally under it, and bear it proudly through your streets, and when we look upon its tattered folds, we can live our battles over again and remember the brave who have fallen in its protection.”

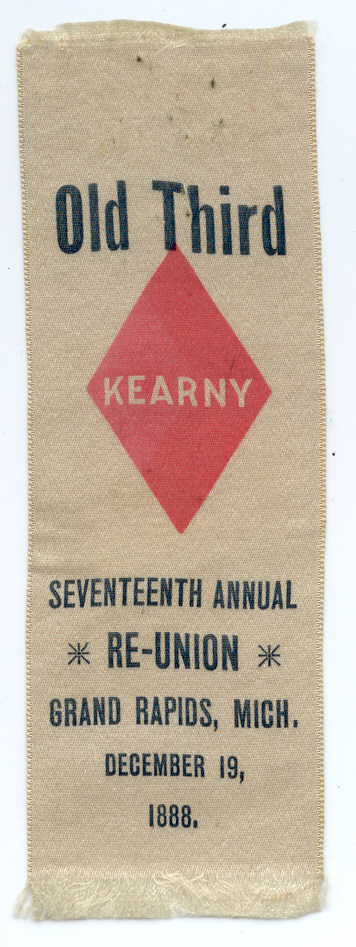

The flag was kept by the “Old Third” for years after the war—displayed at regimental reunions and carried in 4th of July parades—until 1882, when the decision was made to finally part with it. The Grand Rapids Democrat noted that it was by then “in rags and a perfect wreck, being much more tattered now than when sent home from the war in 1863, and then it was shot in pieces.” It would be forwarded to Lansing to join the other battle flags in the Capitol, but, before it went, the “old boys” gave three hearty cheers for the Ladies of Grand Rapids—just as they had done 21 years before—and observed a moment of silence for Maggie Ferguson.

1863

May 1, 2 and 3, 1863: Chancellorsville, Virginia

July 2 and 3, 1863: Gettysburg, Pennslyvania

July 23, 1863: Wapping Heights, Virginia

October 1, 1863: Auburn, Virginia

November 7, 1863: Kelly's Ford, Virginia

November 27, 1863: Locust Grove, Virginia

November 29 and 30, 1863: Mine Run, Virginia

1864

May 5, 6 and 7, 1864: Wilderness, Virginia

May 8, 1864: Todd's Tavern, Virginia

May 10, 1864: Po River, Virginia

May 12, 1864: Spotsylvania, Virginia

Benjamin Morse will win the Congressional Medal of Honor for capturing a stand of colors during this engagement.

May 23,-24, 1864: North Anna, Virginia

May 28, 1864: Skirmish at Tolopotomy Creek,

Virginia.

June 10, 1864: The Third Michigan is mustered out

Federal Service.

Upon the Third's muster-out on June 10, 1864, its remaining men became Companies A, E, I, and F of the 5th Michigan Infantry. As such, they served through the siege of Petersburg, three battles of Hatcher's Run, and the pursuit of Lee's Army to Appomattox Courthouse.

(Pictured here is the staff of the Third Michigan, l-r: Rev. Francis Cuming, Major Stephen Champlin, Col. Dan McConnell, Lt.Col. Ambrose Stevens, Drs. D. W. and his brother Zenas Bliss, regimental surgeons.)

Read the biographies of the men who served with theThird Michigan

Information about the original Third Michigan

Kearny Cross

Click

Volunteer Infantry Co. F

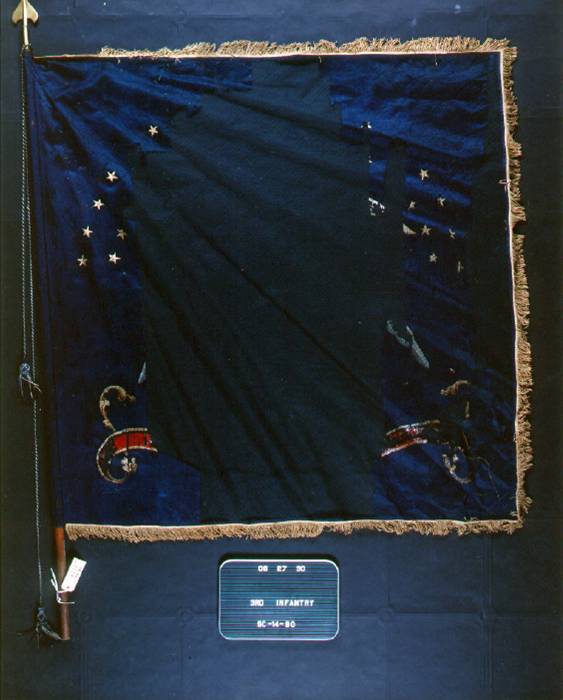

Third Michigan Regimental Flag Third Michigan Secondary Flag

Third Michigan

Find the location where these brave men are buried